My new love affair with a California Extra Virgin

John Gutekanst

I’ll admit one thing: I’m a user. This is a pizza industry term for an independent owner who uses cheese, cardboard, pepperoni, soda, insurance, soap, oil and yes, sometimes even people.

After 15 years in the pizza business, I take pride in using only extra virgin olive in almost every one of the over 100,000 pizzas and breads I bake each year. I coat my pans with this oil for Detroit and Sicilian style for a golden crust. I dimple the oil with my fingers on top of flatbreads and focaccia and pizza Romana. I incorporate extra virgin olive oil into the dough of my ciabatta, Ohio River Valley pan-style pizzas and New York style pies because it promotes elasticity, flavor and crust development at medium to high temperatures. It’s more expensive for me to use extra virgin but my crusts are more crunchy and golden and my breads develop better than my competitors who use cheaper pomace olive oil or mixed vegetable oils made with soy.

Then, last year I got an extra virgin dose of reality. I had just spent the last 15 hours baking and selling breads and pizzas at our local farmer’s market. Back at home, I tore off a hunk of my popular ciabatta bread; this Italian slipper bread is airy, light and perfect for the local chevre I slathered on it. I sat down in front of the television and shoved it in my mouth, chewing as I examined the open crumb helped by using extra virgin oil in this mix. The oil coated the high-protein gluten strands affording a moist, spongy inside which made me moan with pleasure.

Then I turned on a 60 minutes’ episode about the industry-wide fraud in the extra virgin olive oil business. As I watched, my chewing slowed. I felt my stomach turn as if I had just been punched. Allegations unfolded of the deep-seated abuse, deception and outright fraud in almost every segment of the extra virgin olive oil business. I almost spit out the bread that still filled my cheeks, feeling like a lover too stupid to know he had been cheated. Was I part of this deception? I knew my pizzas all contained extra virgin olive oil. But what kind? I had find out.

The next day I picked up one of the large, liter bottles of extra virgin olive oil sitting in rows underneath my dough table. My examination found no country of origin, no method of crushing, and nothing else on the label besides the name. I called my food purveyor and ask about the provenance of this extra virgin oil. He couldn’t tell me, saying lackadaisically, “I have no clue.”

Great. I ground my teeth looking around my store for answers. It turns out that I’m kind of a nut about ingredients. My dough uses the best high-gluten flour I can find. It’s made from hard, red wheat in Manitoba, Canada. I chose our shredded cheese from Grade A Wisconsin milk. It’s manufactured in a level-3 certified processing facility. Purified Ohio spring water goes in my dough starter. Even the stacks of delivery boxes were made in nearby in Zanesville, Ohio. So I have a sense of pride about making pizza. I know I have made this pizzeria the best it can be because of my attention to the quality of raw products. But as I glanced back at that case of oil, I cringed. I never gave a second thought about this damned extra virgin olive oil!

That was about to change. After weeks of research and wrangling with my food purveyors, I decided on a new extra virgin olive oil from a California company called Corto. I already used the Cortopassi family’s tomatoes and tomato sauce on almost every one of my pizzas. I’ve also won eight national and international pizza competitions with their products. But I had to see for myself how they made their olive oil. I was not going to get hornswoggled again. So while I was in California last October, I requested a visit to the company’s processing facility in Lodi.

Exiting the interstate, I enter the narrow roads of Lodi between the groves where walnuts, cherries and grapes rule the land. After a quick introduction at Corto olive oil company, president Brady Whitlow walks with me down the dark alley of his fruit-heavy olive orchard. We pass an old tenant of this farm, a volunteer zinfandel vine rising from the grey soil. Brady reaches up through the olive leaves, pulls a plump Arbequina olive from its cluster and shoves it in my face. His eyes widen. “You know, I’ll remember that first olive crush for the rest of my life, The neon green juice, oozing out, it poured off the line…it was crazy,” Brady says in laid-back Californese, “That day, when we saw that beautiful juice flowing, I screamed, ‘We made that!’

I smiled because Brady, without realizing it, just told me more than any marketing pamphlet or sales associate could ever do. “We made that” was not a question. It was a confident statement made with real passion. I stood in this grove fidgeting with excitement, anxious about the day ahead like I was on the seat of a carnival dunk-tank destined to be dropped into this new world of extra virgin oil. In only a few hours, I would experience a sensory knock-out blow of smell and taste that I will never forget.

But first, I had to learn a little about types of olive oil. The best extra virgin olive oil, called “first cold pressed,” means the just-picked olives pressed immediately, without heat. A machine extracts the juice from the olive flesh. The result is an excellent balance of saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated acids. This cold pressing conserves the vitamin content and at least thirty phenolic compounds attributed with lowering blood pressure and preventing diabetes. Lower incidences inflammation, coronary heart disease and cancers in the colon and prostate are directly linked to the regular consumption of extra virgin olive oil.

For centuries, the first cold press was only made in the Mediterranean region, but now small producers like Corto mix modern growing styles with age-old techniques to produce some delicious oils right here in California.

I follow Brady’s easy stride down the row of olive trees. The tall green Corto building looms in the distance. “We’ve carved a niche in this market with farmers who believe in our strategy and methods,” Brady explains. “We contract with select farmers to grow our olives on their land within a few hour’s drive from this plant to ensure freshness. Today I’ve got you scheduled to meet our field manager, Paul Busalacchi, who’s harvesting this year’s olives up in Arbuckle.” Brady points north, I think. “You can help him harvest and bring back our olives.”

I get back in my rental car and drive north, thinking of how Brady said to “bring back our olives” so matter-of-factly it was like my wife telling me to pick up our kids. I imagine driving with a bunch of Fruit-of-the Loom-like olive children in the back seat fidgeting and asking, “Dad, are we there yet?”

An hour and a half later, I reach the turn off. Paul has guided me by phone, saying I would pass lots of “ammon” groves (I had to ask him three times about this regional vernacular for “almond.”) to one of the sprawling groves that Corto partners with, called Emerald River Ranch, outside Arbuckle. I arrive at a wide view of 480 acres of rolling hills, interspersed with small groves of California Oak, olive, almond trees and yellow fields of hardscrabble soil, gnarly old trees and weeds.

Paul has been farming for the Cortopassi family his whole life. He has also embraced the newest technology in olive harvesting. Large trucks and alien-looking olive harvesters hunch outside the unmistakable dark rows, ready for picking. A small crew tightens screws, fixes broken Oxbo harvesters and waits for olives to haul to the mill. Paul strides over with a burly but cool confidence. With his ballcap and glasses, he carries a Bradley Cooper sniper aura about him.

We get in Paul’s truck with his hyper-active chocolate lab in the back. This isn’t the normal farmer truck that I am used to when I visit purveyors back home in Athens, Ohio. Inside, this huge black SUV looks more like a Secret Service vehicle, with a wall of laptops and screens between the front seats. They tell Paul everything about this grove, from amount of water that has saturated the soil, the composition and status of olives in each row, to how many trees are picked and how many are left. I buckle up as he takes me to meet the olive harvester already working in this massive grove. My first question was self-serving.

“So are there any bears around here?” I giggle nervously.

“No, John,” he replies patiently. “But there are a lot of rattlesnakes, coyote, and wild pigs.” I try to look him in the eye to see if he’s kidding, but his dark sunglasses only reflect my image. He stops the truck and points. “See all that damage to the earth, under those trees? That’s from wild pigs digging.”

“Rattlesnakes?…” I mumble.

“Don’t worry bud, we haven’t seen any this year…yet.” We head uphill.

At the highest point in the grove, olive trees spread in rows, trimmed and trained to grow along wires. “We grow our fruit closer together so that it is easier to harvest,” Paul explains. “High density olive farming started in Spain decades ago. Here in California, it’s been used for 22 years.” He adds that because the company purposefully approached farmers within hours of their Lodi mill.” Pointing to a truck rolling through the dust to the main road, Paul says it will reach the mill in an hour and a half.

“Why is that so important?” I ask.

“The longer those olives sit, the more they oxidate, losing all the nutrients and brightness of the oil.”

Meanwhile, I can’t stop looking at the height of these trees. I don’t want to use the word “runt” because Paul looks like he could take me. “I’ve seen olive groves in Europe. Why are these trees so small?” I challenge, trying to impress him with my worldliness.

“We train the trees to ten feet tall,” Paul responds. “We use a drip tape and soil probes to water the roots which gives nutrients the shortest amount of time to travel from root to the fruit clusters. This ensures consistent ripening of all the fruit on each tree.”

As I look down the rows, I am struck by how these trees resemble the French “espalier” method of training apple and lemon trees. I once viewed the method in the gardens of the Biltmore House in Asheville, North Carolina. Those fruit trees are planted next to brick walls to take advantage of the heat radiating during the cold winters.

We exit the truck in the middle of a grove and walk down a row. Paul runs his hand along the leaves. “These trees thrive on this hardscrabble,” he says as he kicks a divot into the rocky soil with his toe. “Here we are growing ninety percent Abequina, five percent Arbesana and five percent Koroneiki. They flower in May and by growing different varieties, we ensure the majority get pollinated.”

These olives are smaller than marbles. This is not at all what I expected. I said I thought olive oil was from larger, more ripe olives like the giant brined olives in the store, but Paul corrects me.

“It may be surprising, but these small olives add up. Each of these trees will produce a half-liter of olive juice.” Staring at the tree in front of me, I envision the whole harvest of that tree filling up just one jug of the crummy extra virgin olive oil I previously used at my store. Still, I’m not satisfied.

“But these olives don’t look ripe,” I protest.

Paul pushes a greenish-violet orb into my face. His farmer fingernails are dirty. “That’s the beauty of this fruit, overripe olives are spent and bruise easier.” Paul explains. “Ripe olives oxidize and then ferment, that’s when they fall off their perch.” He presses the olive to demonstrate how it is full of anti-oxidants, which are not only great for humans but protect the fruit from the sun. “Animals and birds find this green olive too bitter to eat. This bitterness, along with the fruitiness of the oil, is what we want”

Suddenly Paul jumps to the side. “There he is,” he says, pointing down a row. The noise gets increasingly loud and sounds exactly like the World War II Sherman tank in an old war reel. I expect to see General Patton up top instead of the cigarette-smoking driver in a large glassed box. I turn to ask Paul another question but he’s now scrambling up the side ladder of the harvester. He waves me up. He yells that this giant yellow Oxbo harvester doesn’t actually pick olives, but gently shakes the tree with what look like bowed PVC pipes powered by hydraulics. Essentially a modified grape harvester, it must be the most efficient olive harvester on the planet. Or at least it better be, because these machines can cost up to half a million dollars.

Now I’m standing on top of this ominous machine which straddles an entire row of trees. My white-bones cling to the yellow railing as I’m seizure-jerked quickly in every direction. Even my lips itch from the shakes as I realize there is zero chance of looking guy-cool on top of this giant. It chugs along and sounds like a hundred laundromat dryers filled with tennis shoes. A “U” shaped cavity in front shakes the leaves and branches that pass below me with just enough pressure to knock the olives off. The olives then hitch a ride onto a series of conveyors and eventually shoot across the top of the olive row like a cartoon rainbow. They land in a bin driven by a tractor on the other side. This loud monsters’ mouth reminds me of Sigourney Weaver’s lamprey-like enemy in Alien, but it’s built to do as little damage to both fruit and the tree as possible.

Within twenty minutes, my previous three cups of java combined with insufficient “sea legs” have me shaking like a Boston subway rider. I’m now mesmerized by this steel nest of hyper-activity passing the greenish-violet olive rainbow through the air and into the bin on the other side of the trees. Olive trees stretch to the horizon, below the blue-purple Coast Range to the west. I feel like a like kid again, one in a tank or on a freight train.

“This is serious business,” I shout to Paul. But he is already on the ground. I climb down like a dog who has lost his owner and walk towards him with wobbly legs. The massive machine slowly fades in volume as it chugs down the row.

Our feet crunch through the aftermath of this olive chaos, with only a fog of leafy confetti floating in the air. The trees are less droopy and more angular, with a few broken limbs but no olives to be seen. This grove feels spent and lonely, like a station after the train leaves. Paul explains that after the harvesters go through the grove, they spray a fine mist of copper on the trees to heal any wounds the harvesters create. “Rain is a big issue here at harvest time,” he adds while looking up at the dark clouds. “The rain will permit bacteria to spread into any small wounds the harvester has made, making the trees sick. We’d rather have healthy trees, because healthy trees mean a healthy harvest and better juice. If we have sickly trees or a grove that is not producing the best olive oil, we’ll forgo this harvest and wait another year.”

I stopped walking. “You mean you would sacrifice this grove for a few trees?” I asked incredulously, thinking about my own business and the perfectionist chefs I’ve known.

“It’s not just a few trees, John,” Paul responds. “It’s thousands of olives and gallons of juice that effect the taste of our oil. In the end, it’s our reput…”

“Dude, I know where you’re going.” I interrupt. “You sound like all the great chefs I’d worked for in the past 30 years. They taught me that every single component in each dish was made from the best ingredients and cooked perfectly, or the dish didn’t get made at all.” I’d seen a great French chef throw perfect-looking entrée plates at the wall instead of releasing them to awaiting diners, just because the carrots were overcooked. I saw an Italian chef dump 20 gallons of seafood bouillabaisse on the kitchen floor during service, just because someone put the mussels in too early. Apparently, this habitual pursuit of perfection was not dead, especially during these days of low profit margins, corporatization and culinary sameness. I just never knew I would come across this attitude in a dusty place called Arbuckle.

I follow Paul down another unharvested row. He reaches into another olive-heavy tree and dangles a small bunch under my nose.

“These olives that are just turning from green to black, ” he says. The degree of excitement shows in his eyes like it does when my kids bring home a school project. “Right now is the peak of their flavor. Today this whole grove will be picked, transported, cleaned, pressed, milled and stored within five hours of picking. This is how we know we have the most consistent extra virgin olive oil we can make.”

I nod, feeling guilty for shoving a few handfuls of fresh olives in my pockets, to cure when I get home. “If you follow this harvest, you’ll probably have time to taste their juice.” Paul says. He may be trying to get rid of me but at this point, I don’t care. Like a base runner rounding third, I am grateful to reach home and finally taste this product. My eyes light up and my pace quickens back to my car

When I arrive at the mill I meet David Garci-Aguirre, vice president of operations and blend master of Corto. He is standing next to the door of the giant crushing room.

“Are you ready to experience something insane?” he asks. His brown eyes broaden like a kid about to play practical joke. He waves me over to the door, opens it, and follows me in. The sound of a freight train louder than the harvester in the field hits me as I walk further onto a catwalk. The unmistakable essence of extra virgin olive oil wafts about this room like a beautiful ghost.

“Oh, my god.” It is all I can muster.

“The micro beads of the olive juice are everywhere, John.” David yells over the noise, his face shining and giddy. I breathe in more air, tasting tomato, pear, and asparagus. I am now in a perfect place filled with memory, pleasure and speechless joy. This new sensation of olive “air” is so magical, I want to breathe this for the rest of my life.

“You should see your face.” David says that triumphantly.

“Sorry.” I look down through the catwalk at this pit of mechanical monsters chugging away.

“No apologies, John,” says David agreeably. “Everyone looks like that when they experience this. It never gets old.”

Reluctantly, I follow him back into the office, awestruck at my first immersion in olive oil “air.” David explains that his interest in olive oil grew out of his work in metals as a teenager. In his 20’s he made a mobile olive oil press, and visited wineries to press the olive trees growing alongside the grape vines. He walks me down to the loading dock, where I don a white jumpsuit, booties, hair and beard net.

“Hey Santa!” David jokes. I offer up a condescending chuckle.

Two trucks have just arrived from the broad plains of the big valley. It’s my load from Arbuckle.

As I walk towards them, a loud thumping mass of machinery surrounds me with the sizzle of water spray, the whirr of conveyors and the patter of feet on catwalks. Millions of olives pitter-pat through this massive washing and sorting pad.

“We have to be sure our olives are clean, ripe and free of all deleterious material that would ruin the juice,” David yells, snatching an olive from the nearest conveyor. The sorting pad is as open as the big valley itself, but now it’s as loud as Cape Canaveral during a shuttle launch. The truck drops its load from the bottom of the funnel-like bin into a pit fitted with large black pipes. The olives pop up and wash into a mesh of corkscrew-shaking conveyors designed to knock off any remaining twigs, leaves and dirt. The conveyors break up remaining clusters and throw them back into another washer.

I am so engrossed in the washing of these green and purple marbles that I lose David and see him climbing higher into the belly of this massive beast. “This is the color sorter. It’s the same technology we use to harvest only the ripest tomatoes in the field,” He yells down. “The lasers detect all off-colored olives, sticks, leaves, frogs, bugs or even misshapen olives and mummies,” Says David handing me what looks like a large hard raison.

“Mummies?” I ask, shaking the vision of King Tut with a beard net from my head.

“Yes, my man,” David says. “A mummy is a shriveled olive that has stuck to its stem and wintered on the tree, only to be harvested a year late.” He shows me what looks like a very dark, hard raisin. “If even one percent of stuff like this gets through to the press, it will ruin the olive oil’s taste.”

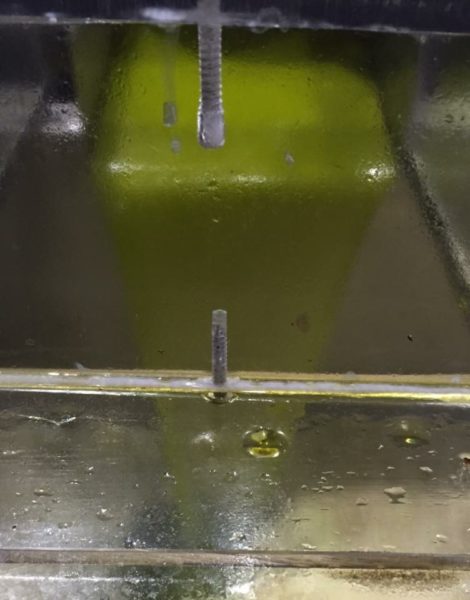

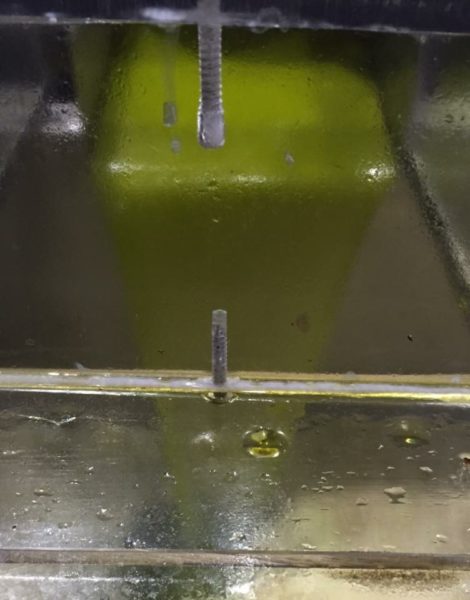

He takes me back inside the crushing room, where I see the magic happen. These are my Arbuckle olives becoming juice, juice becoming oil. The whirring of the centrifuges and that heavenly smell of extra virgin micro beads brushes by me like an airy ocean spray. David takes me over to the long olive crushers, also called hammer mills.

To my surprise, he tells me that olive oil is essentially tasteless. It’s the flavor from the flesh that contains the nutrients as well as flavor. “That’s why we need to let the juice and flesh mingle for a while.” David runs his hand along the crusher. It looks like a small submarine. He explains that another machine, called the “malaxer,” is where the color, flavor aroma and nutrients integrate and unite in the micro-beads of oil. Bright gold liquid spews from the malaxer’s stainless-steel mouth. It looks like a delicious waterfall of wet lemon cream.

“Why is it so thick? I ask.

“It’s just the start, my man.” David explains, pointing at another giant boxy machine. “It’s gonna be sent to this last centrifuge for another spin at 7000 RPM. This is the final separation.” David smiles and fidgets with wide eyes as he stands on one leg, then the other in anticipation. I can’t help thinking of Dr. Frankenstein.

He squats down to where a small spigot pours a little oil into two cups. We toast to today’s crush. As I slurp, my eyes close and I see those thousands of green-purple Arbuckle olives as the juice slips down the back of my throat. I taste fresh cut grass, then butter, and then tomato, pepper, and pear skin. A biting sensation in the back of my throat follows. It’s almost like aspirin residue but it dissipates quickly and leaves me wanting more. David is in my face now, with his pencil-thin mustache and meshed hat. And that smile.

“Whatta ya think? Huh? See, it isn’t greasy, is it? “

“You’re right, it isn’t.” I lick my lips.

“You see John, greasiness is a sign of oxidation. Oxidation occurs only in ripe fruit. Ripe olives are literally fermenting. They produce pungency and bitterness because of the presence of bacteria or mold. This smell is what we call ‘Fusty’-that smell of sweaty socks or old gym clothes, because it has gone through an advanced stage of anaerobic fermentation.”

“But isn’t ripeness good for fruit?” I ask.

“Yes, for bananas, apples and oranges,” Dave says patiently. “But olives are different. “If the oil has undergone anaerobic fermentation, it will taste like vomit, bad salami, manure or baby diapers.”

David leads me around the corner to the settling room, an imposing 40 foot-high-ceilinged warehouse filled with tall tanks like a stainless-steel redwood grove. As each lined tank fills with extra virgin olive oil, it fills with nitrogen immediately, to keep oxygen from meeting the oil. The olive oil air has disappeared and I feel spent, like I just got off a roller coaster of flavor. I want to go and live back in the crushing room, but I say my goodbyes and drive north with new respect for the olives groves I pass on the way.

Just four days after visiting Corto, I am baking in my pizzeria in Athens, Ohio with my managing partner, Joel Fair. It is 3:30 a.m. on a Saturday morning and I’m just five hours into my baking routine. I’ve finished the couronnes, baguettes, puff pastry, sourdough boules, and long schiacciata or flattened pizzas. They’re piled on my wire racks, cooling.

Now the first fougasse flatbread appears from our conveyor pizza oven. I cut this loaf 13 times to form a leaf. The holes enable a faster cook time and make this loaf strikingly beautiful. This first loaf I check is fragrant and steamy. The tanned brown crust sparkles from an initial coating of olive oil, coarse sea salt, and dried herbs.

In the next hour, I will bake 160 more of these loaves. I dip the brush into my golden-green olive oil and dab a thin coat on the crust, over the crunchy salt. This bread is an addiction to many of my customers, but none of my bread junkies can pinpoint why. Is it the flour, the salt, or the herbs? No. Some refer to the taste as intoxicatingly garlicky, but they are wrong. It’s the real extra virgin olive oil and lots of elbow grease.