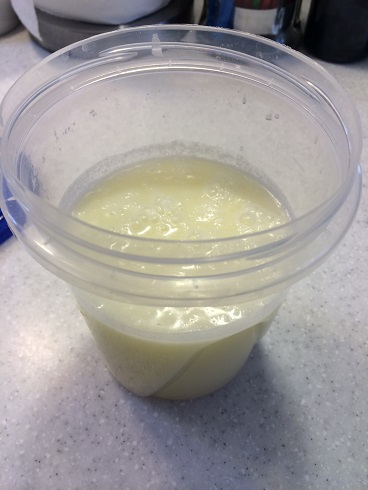

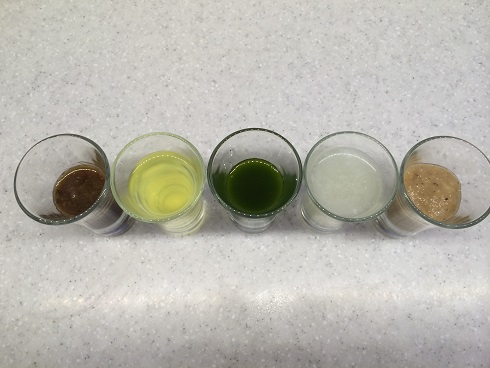

Of all the lame-brained ideas I’ve obsessed over, this is the top of the top. That said, I just had to go with the idea of taking the raw ingredients of a beautiful pizza and building the flavors up from scratch to actually taste like a pizza but only in its purest, liquid form. (Above is my two-week labor of love which, my wonderful wife who is my harshest critic said, “…tasted exactly like a fabulous…pizza.”)

Many chefs are breaking certain iconic dishes down only to built them back up using cooking methods, chemicals and faux ingredients to re-create said dish in another, wacky way. This is especially true for challenges in cooking shows to test the flexibility of a chef. It is great to think of any dish in a different way by throwing out the visual, historical and textural preconceptions by interpreting a culinary item on taste alone. This fun and challenging concept for a pizza was done without the use of gels, chemicals or fancy kitchen machines. I also made a promise that for the sake of your sanity and what’s left of mine, I promise you that I will, at no time use the term; DECONSTRUCTED.

The pizza I targeted is a Neapolitan style pizza topped with Prosciutto di Parma and Parmigiano Reggiano. I cooked the pizza above at 800 degrees and it demonstrated that perfect Neapolitan taste. (Dontcha just love how that Prosciutto melts.) I now had to replicate the wheaty char of grain, the sweetness of tomato like the San Marzano’s above, followed by the ultra-umami found in Parmigiano Reggiano, the salty-fat-fruit of Prosciutto di Parma, the vegetal kick of fresh basil and the milky mozzarella.

First, the Tomato:

Every year at the height of tomato summer, I get the largest, juiciest locally grown, heirloom tomatoes and freeze them. Then, in the depths of winter, I take them out and just put them in a bowl to defrost. Letting gravity and warmth transform these beauties is amazing and quite simply the best way to get tomato water from these beasts. I then create a a winter gazpacho with fresh herbs, diced vegetals and crabmeat.

For this project the tomato water came from three distinct heirlooms; Sweet Azoycha Russian yellows , Green Zebras and Cherokee Purples, all organic and locally grown by Green Edge Gardens in Amesville, Ohio.

When each tomato started leaching the almost colorless water, I drained each tomato group a separate bowl and let gravity continue to push the liquid out more.

Then I was ready for just a little salt and a few days flavor-meld in the fridge.

For the Parmesan:

This may seem to some cooks as particularly wasteful but I gotta tell you, its worth it! You’ve not lived until you do a shot of Parmigiano Reggiano water! The simple act of separating the fat and solids by grating the parmesan and throwing it in boiling water, turning off the heat and letting time and temperature pulls the strong flavor out of the solids and opens a whole new culinary dimension for this king of cheeses. You can take this liquid and make ice cream, gels, “Cheetos-like” crackers, dashi or even make parmesan caviar with the help of sodium alginate and calcium chloride.

I placed about eight ounces of grated parmesan, including the rind, into four cups of just-boiling water then turned the heat off to let it cool while stirring constantly.

When the mixture cooled enough, I placed it in the fridge for three days to meld the flavors and separate even more. After a final skim, it is ready.

For the Crust:

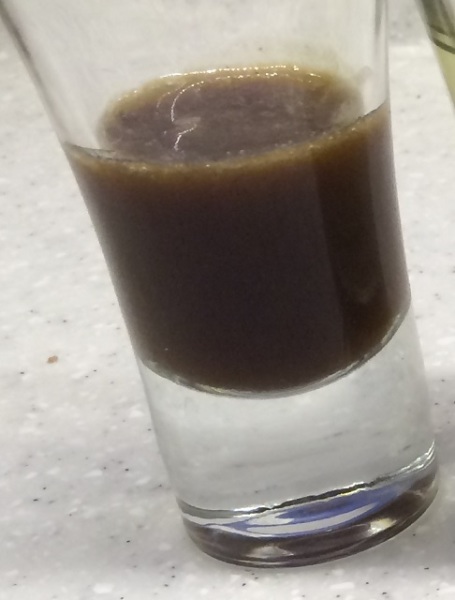

Finding a wheat taste in liquid form was my toughest challenge so I opted to start with the grain in a harvested berry form. The local spelt berries are grown twenty-two miles away in Chesterhill, Ohio were a perfect start. The Amish grow copious amounts of this deep-tasting grain and they harvest it with horses. My plan was to first toast the hard outer shell it under high heat then braise it to cook the grains, or berries. This released the earthy, chocolate-tea-toastiness so prevalent in this spelt. After toasting, I covered them with water and boiled them over medium high heat for three hours until the endosperm popped through the hard husk of each kernel.

The vision I had in my head compared to what was happening in reality was very different while rendering the spelt into liquid,The plump endosperm that popped through the bran and charred outer shell of each kernel was magnificent and bloated exposing the white glutinous heart of each kernel. I had to concede that this gluten was an integral part of the fluid I was making and no washing or straining would get rid of the gravy-like liquid. Even though this was not what I had envisioned but the taste was magnificent and I knew I had nailed it. (I even made a killer salad out of the berries.)

So I added water to it and blended it again then reduced the liquid for thirty minutes, straining again with a finer and finer sieve. After cooling, the presence of the gluten and bran made a thicker liquid but still had the taste of a hearty, toasted wheat. I was finally there.

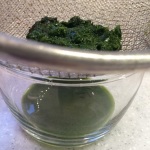

For the Basil oil:

I took a handful of basil then cut and mashed it, adding extra virgin olive oil. I then held it to macerate for five hours then strained it. I could have made it more bright green by shocking the chlorophyll in the basil with heat and ice water but I had to get the kids from school.

And for the Prosciutto di Parma:

I usually make some great cracklings out of the shank product that I get from each prosciutto leg but I also make a killer reduction of this, the king of hams. I first took the shank and cubed it then sautéed it on medium high heat with a tablespoon of extra virgin olive oil to brown each chunk. Then I added a mirepoix, (celery, onion, carrot).

When all the flavors melded at medium high heat, I turned the heat down and added one cup of chicken stock and two cups water to cover the mix. I left it to gently simmer and breakdown for 20 minutes before extracting all the solids. This left me with a liquid which I reduced on high heat for 10 to 15 minutes until it was thick and tasted like the purest essence of Prosciutto di Parma!

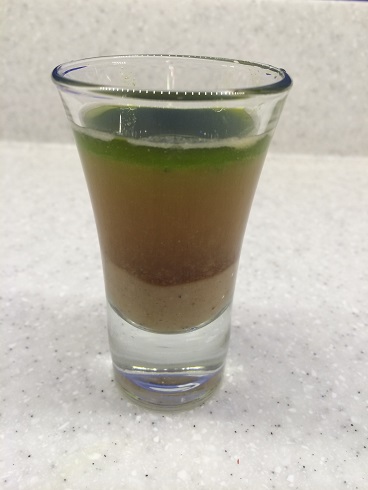

My first few attempts at placing this flock of liquids on a plate, in a soup bowl and even in a shot glass failed miserably until I found the right layering. I am no freakin’ scientist but I soon found that each liquid had certain weight and density that pushed downward from gravity.

So after many trials, (massive fail on left), I found that the placing spelt on bottom followed by Prosciutto di Parma gravy, then the Parmesan water followed very gently by the tomato water and topped with basil oil was the way to go. Because of the strong flavors in the Parmesan and prosciutto liquids, I added more of the nuanced tomato water for a better balance.

Finally, I turned the mozzarella into the most luscious liquid of all. Just by melting it in a pan, it liquefied and completed this wonderful shot of pizza with a blanket of goo. (As I proudly introduced this liquid to my employees, they asked where the vodka was- maybe next time!)